https://news.fitzrovia.org.uk/category/history/

During the Second World War the people of Fitzrovia, like many other Londoners, insisted on using the Tube stations as bomb shelters,in defiance of government deterrence. They quickly forced the authorities to back down and accept what was in effect a people’s occupation of the Underground.

During the intermittent London bombings of 1917 people had sheltered in the Underground; so it was expected that Londoners would head to the Tube when war broke out again in 1939. As Mike Horne explains in The Northern Line:

This time round the government feared that a ‘deep shelter mentality’ would develop, with people refusing to come out. At the outset of the war the use of Underground stations as shelters was therefore banned. (54)

But when the Blitz began Londoners, rather than accepting the official line that the Tube should remain solely a transport network to ensure movement around the city, insisted that it should provide refuge in time of urgent need.

The government dithered over the question of deep level shelters before the War and for many months after it began, doing nothing to provide them. Some MPs pressed very strongly for government action to protect the population, as did Megan Lloyd George. But others such as Sir Ralph Glyn, speaking in a Civil Defence debate on 5th April 1939, opposed the provision of deep shelters in tube stations as potential hindrances to the flow of traffic. Sir Ralph was concerned that the debate too much favoured the population at large:

There is a great danger that people will get an impression … that we are paying too much attention to the protection of individuals here, and not giving sufficient attention to what really matters most—our offensive and defensive power.

Sir Ralph also believed in looking ahead at future uses for such shelters:

If you are going to make deep shelters … you must devise shelters which will bring in some sort of commercial return in time of peace, such as car parks …

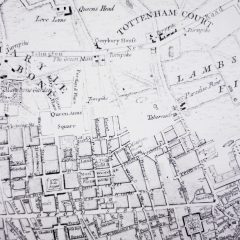

But when the bombings began in August 1940 the people simply decided that they and their families felt safest in the Underground and occupied the tube stations. Helped by political activists, they ignored any attempts to stop them. Tottenham Court Road, Goodge Street and Warren Street were all occupied and became heavily used. Ted Bramley of the Communist Party, in the pamphlet Bombers Over London dated 12th October 1940, declared:

Three times the authorities said that the Tubes must not be used as shelters. But the people went to the Tubes. At many stations police and officials barred their way, gates were closed; but at Warren Street, Goodge Street, Highgate, etc., gates, police and officials were swept aside and every inch of stairs, corridors and platforms taken by the people. (p.10)

The people’s will was acknowledged in Parliament. By October 1940 tube sheltering was starting to be organised to make the best use of available spaces.

Once stations were being used by thousands of people night after night during the Blitz, it became desperately urgent that facilities should be provided. Hundreds of recumbent people were squashed against each other without any bedding to provide a minimum of comfort; they even lay on the rails in the disused stations. These extreme conditions were greatly worsened by the absence of sanitary facilities; the smell must have been almost unbearable. By January 1941 the work to equip the tube stations was well under way, with three-tier bunk beds provided. The Minister of Health, Malcolm MacDonald, described the improvements: sanitary equipment was provided, ventilation and heating was looked at, and overcrowding was reduced by encouraging people into less-used shelters. First-aid posts operated in the larger shelters, with a sick-bay, a medical officer and a nurse in cases where patients had to be isolated.

Local resident, Max Minkoff, had vivid memories of sheltering on the platform in Warren Street tube station, recalling that his family were allocated bunks in the station by organisers: “we … had to go to the underground in the evening to get our bunks, we had to go seven o’clock, six o’clock, whatever it was, straight after work.”

Max’s father stayed at home with one of Max’s brothers, sleeping in the basement under a table. (Jewish Museum audio 319) The tube trains carried on operating while the platforms were occupied. There was conflict over space despite the best efforts of the marshals: my mother, Rebecca Coshever, then a girl of fourteen who lived in Howland Street, remembered arguments breaking out with her families’ regular platform neighbour, a German woman, over infringements caused by the woman’s many belongings overflowing into their own little patch.

The Tube sheltered up to 177,000 people a night during the War, while continuing to circulate people around the city almost as before. During the war, eight new deep shelters, sheltering up to 8,000 people each, were eventually constructed under tube stations including Goodge Street; but they weren’t opened to the public until 1944. The Tube played a vital role in the West End but it was far from being able to protect everyone; many people had to rely on Anderson shelters in back gardens, indoor Morrison shelters or other types of surface or basement shelter.

The Tube shelters became a part of wartime mythology, drawn by Henry Moore and locked into generations’ memories. Domestic life, at least for some Londoners, took root below the street surface. And for communities in Fitzrovia the underground shelters were a vital refuge: the locality, abutting major railway lines, was heavily bombed both in 1940-1941 and in the doodlebug era of V2 bombings in 1944. The destruction included the bombing of Maples, the big furniture store in Tottenham Court Road, and much of Howland Street, where my mother’s family had lived. For many people in Fitzrovia the Tube became a world in itself; a world that ordinary people had claimed and helped to shape.