In February 2017 the hashtag SpyWaiter became a Twitter meme after President Donald Trump and the Japanese Prime Minister, Shinzo Abe, were observed by diners and staff at Trump’s Florida resort, Mar-a-Lago, discussing North Korea’s provocative test firing of a ballistic missile into the Sea of Japan, immediately after the incident happened. Comments were made on Twitter and in the news on the startling lack of security surrounding this urgent discussion and the consequent scope allowed for snooping by outside agencies on the arrangements for dealing with the crisis. According to thinkprogress.org, a progressive news site, “Trump … discussed sensitive national security matters in front of waiters and diners who were later able to describe the scene ‘in detail’ to reporters.”1

Although no proof has been published that waiters were actually spying at the resort, speculation flourished. A Twitter user, @TrueBlueLiberal, circulated the resulting meme a few days later on 16 February: “If you’re Vladimir Putin, you know what time Trump is dining at Mar-a-Lago on Saturday to time your next provocation and unleash #SpyWaiter.” More mileage was made, on news sites like Politico and elsewhere, from the rumoured lack of vetting of Mar-a-Lago’s ‘guests’ – who pay a huge subscription fee to use the resort – and Trump’s hiring as recently as 2016 of foreign workers, including waiters, at Mar-a-Lago on temporary visas and modest terms of pay.2

The Trump-related ‘spy waiter’ narrative is backgrounded by suspicions of the conduct of Trump and his associates in the White House, especially that there was collusion between Trump’s circle and Vladimir Putin’s in order to disrupt election processes and swing the election to Trump. Political uncertainty arising from questions about the administration’s legitimacy, and various actions and sayings of President Trump, has been perceived by many as weakening the political position of the United States and even threatening its status as the number one global power (Trump’s recent decision to exit the Paris Agreement on the environment has harmed that status even more). The wider global background to these anxieties has been the rapid rise of large industrialising nations, above all China which is now the world’s second economic power and will probably soon overtake the US at number one, portending changes in global alliances and highlighting a gradual US decline in political influence across the globe.

The #SpyWaiter story has retreated from the forefront of the news, pushed out by a relentless flow of security scandals involving the Trump administration. However, it continues to be interesting for historical resonances with European politics one hundred years earlier. This American waiter espionage story relates not only to the international political landscape of the early twenty-first century but also to that of the early twentieth century when similar stories arose in Britain. Although emerging from widely differing political scenarios, both sets of spy narratives can be seen as alarmed reponses to political shifts that have been perceived to threaten national identity.

The instability in the present position of the US can in some respects be compared to the instability of Britain’s position during the period before the First World War, when the balance of powers in Europe was in flux, Britain and its Empire was similarly in a period of slow decline, and Germany, a fast-rising industrial and military nation with increasing global ambitions, was posing an economic and political threat to Britain. Uncertainty about Britain’s role as a Great Power was instrumental in raising suspicions about, and hostility to, German and other foreign immigrants to Britain, at a time of high immigration into the country; immigration is similarly a hot topic in both the US and the UK and a major preoccupation of the Trump and May administrations at the moment. A century ago, Britain’s anxiety about its future had crystallised into paranoid-seeming fears that the many German waiters in London and other cities were hostile agents.

In both cases these scapegoated groups of immigrant catering workers, often struggling on the economic margins, were vehicles for the airing of public and media anxieties about national identity rather than actual agents of espionage or saboteurs. A realistic view of Britain’s immigrant waiters and other catering staff a century ago is that their economic movements presaged some activities of the EU and posed a challenge to nationalism as these workers freely circulated Europe in search of job opportunities and training. And it is in a period of increasing withdrawal and nationalism that the theme of ‘spy waiters’ – albeit half-jokingly – has again appeared in the news.

The 1901 UK census suggested a total of 8,634 foreign waiters in Britain, of whom 3,039 were German while many others were Austrian, Swiss, French or Italian. The catering industries in London relied on migrant labour more did than most other industries; and catering staff were highly mobile. The continual flows of migrating labour between and around the Continent and the UK seemed to anticipate aspects of the European Union. Panikos Panayi stresses this inter-continental flow: “The European-wide nature of this business … involved people on all levels of this industry moving between European states, almost as part of an apprenticeship system.” 3 Before 1914 the most important group was Germans, although Italians, Swiss and French waiters were also numerous in London’s West End and elsewhere. There was constant movement of workers between Britain and their homelands. Before the Aliens Act of 1905 there were no immigration restrictions and people could arrive and leave with no hindrance.

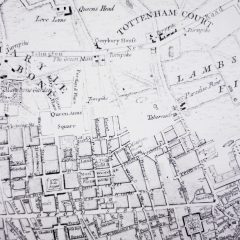

Waiting and chef-ing were, and often are now, sweated trades subject to very long hours, casual employment and poor pay and conditions. The large percentage of recently-arrived immigrant catering staff in Britain’s cities a century ago tended to make exploitation more likely. A small minority of waiters or chefs who worked in first-class restaurants could do well: a head waiter at a top restaurant could make up to £10 or £12 a week, a huge wage at that time. However, small restaurants might pay £1 to £1.50 a week – if they paid regular earnings at all. It was quite common for immigrant waiters to have no basic pay, relying on tips. Waiters worked 12 to 14 hours a day and conditions were sometimes worse than poor, with little ventilation in kitchen areas and nowhere for staff to have meal breaks or change into uniforms. But even apart from cheapness of labour there were advantages in employing foreign waiters: they were well trained and could speak several languages. Fitzrovia near London’s West End, a centre of German migration, played a vital part in the Europe-wide catering apprenticeship system by giving a home and employment to the German waiters and cooks that thronged the neighbourhood due to the low rents and numerous job opportunities there. In fact, Charlotte Street around the turn of the twentieth century was known by some as ‘Charlottenstrasse’, reflecting Germans’ predominance in the area.

However, the increasingly tense relations between Britain and its economic challenger Germany from around 1900 fostered an atmosphere of conspiracy in which fears of German spies on the loose in Britain started to flourish. One of the earliest and most persistent disseminators of German spy scares was William Le Queux, a journalist and amateur spy who was actually to play a role in setting up a voluntary Secret Service department before the First World War, working with Field Marshal Lord Roberts who shared Le Queux’s convictions that Great Britain was about to be invaded by Germany. Together they produced a fictionalised account of a German invasion, rich in detail, that was serialised in the Daily Mail during 1910 and proved hugely popular. At the same time, numerous writers were publishing spy novels, the first being Erskine Childers with The Riddle of the Sands in 1903. Although Le Queux’s counter-espionage work searching for German spies was never taken seriously by the British government, Le Queux had influential supporters whose conviction that Britain, unawares, was host to a vast network of German spies gained considerable exposure in the newspapers and encouraged fears of espionage and invasion.

In the years leading up to and throughout the First World War there was increased public hostility towards foreign workers as a whole, most of all Germans. Workers’ frequent movements between England and Germany no doubt fuelled concerns that some were passing on secret information. They were sometimes accused in the press of being spies, above all in the Daily Mail. Waiters came under particular suspicion because they could get close to those in powerful positions at their dining tables and eavesdrop. The paper went as far as to tell readers: “Refuse to be served by an Austrian or German waiter. If your waiter says he is Swiss, ask to see his passport.”4

In 1905 there was an early ‘spy waiters’ scare. The Daily Mail reported on 10th May that, at a meeting of the Royal United Service Institution, Admiral Sir N. Bowden-Smith had asserted that “danger existed in the many thousands of foreign waiters who might be used as spies.” But a responding article in the Daily Mirror, more sympathetic to workers than many papers, was dismissive of these claims, reporting that foreign waiters, when interviewed, seemed bemused by spying accusations. (11th May 1905) The Mirror made the case that most waiters were either naturalised citizens, married to British women, whose sympathies were with their new home countries; or they were in the UK to avoid military service in their home country and were obviously disinclined to help that country.

Generating a little false sensationalism, the Mirror article reported that, “Only two authentic cases of spying by waiters were to be discovered, and they were both as personal, not as public, agents.” The ‘spies’, in other words, were not foreign agents after all, but, in one case, a waiter who had come to ‘spy out’ business opportunites, and, in the second, a man who was looking for someone who had wronged him, to be revenged on him. The Mirror, though, also revealed that “Scotland Yard has a number of detectives among the foreign waiters”, and suggested that the police forces of other countries might also have infiltrated their numbers, tending to reinforce a sense of danger associated with these workers.

After the war began, the rhetoric against German immigrants, naturalised or not, increased in volume and vitriol. The Mail of 16th October 1914 was claiming that: “The presence in our midst of over 40,000 Germans and Austrians … must be a source of constant anxiety to the public … many of these people are in a favourable position to obtain information. Nor has any precaution been taken against the multitude of Germans employed in our British hotels … these alien staffs are usually to be found at those centres where naval and political intelligence abounds.” Newspapers like the Mail also consistently attacked government lack of action against naturalised German citizens although politicians argued this was impractical and unnecessarily harsh.

Even though no real case of ‘spy waiters’ came to light, this issue rumbled on until after the war, excusing some harsh treatment of German immigrants and others, including mass dismissals, deportations and internments. Unions such as the catering workers’ spoke up for their foreign colleagues against the prevailing public dislike. The National Union of Catering Workers was formed during the First World War as a fighting trade union; its headquarters was close to the West End in High Street, Bloomsbury. The National Union of Catering Workers aimed to: “obtain a minimum wage (varied according to the grade of worker), shorter hours for all, and substantial concessions regarding holidays.” And the NUCW was strongly internationalist: its journal, The Catering Worker, was written partly in French to reflect the nationality of many of its members. In wartime it worked to defend its members against the strongly nationalistic and xenophobic tone of the times.

It appears that waiters have once more been touched by the finger of suspicion, this time in Trump’s America. It remains to be seen whether these particular espionage stories contain any truth as the Trump administration leaks information from every pore. A racing certainty is that the Mar-a-Lago catering staff are as relatively low-paid, insecure and unorganised as were their predecessors one hundred years before; and that their presence is as liable to be exploited for partisan political reasons as the German ‘spy waiters’ of Britain’s First World War.

Skip to content