Sidney Spellman and the 43 Group

There was a large Jewish community in Fitzrovia by the time of the Second World War. They were far less exposed to anti-Semitism than the Jews in the East End who were the targets of Oswald Mosley’s British Union of Fascists. Besides being a much smaller group than in the East End, the Jews in Fitzrovia had found themselves in a very ethnically mixed part of the city. But as the 1930s progressed, strong forces threatened Jews not only in Germany and other European states, but at home in London and other British cities. The biggest home-grown Fascist movement was Mosley’s BUF, which operated mostly in the East End but had several offices in the West End, including a recruiting office in Regent Street.

Some Jews living in Fitzrovia and the West End, like many other Londoners, were mostly concerned with avoiding ‘trouble’ and going about their daily business without interference. In my own family of Fitzrovia tailors this might have been true to judge from the memories of my mother’s cousin Henry, who was a small boy in the Thirties. The people he knew were “humble and timid people”, he says, who were not well-informed about the political situation and not prone to getting into fights with anyone. But by 1936 the feelings of unease and fearfulness at what was going on in Nazi Germany and at home had built up into a powerful sense of threat that was causing constant pressure on the Jewish Board of Deputies to take action.

A Jewish Defence Campaign set up by the Board of Deputies was announced in the Jewish Chronicle on 24th July 1936, less than three months before the Mosleyites tried to march in Cable Street. The Defence Campaign aimed to oppose the attacks on Jews by reasoned arguments against anti-Semitism and the presentation of the positive contribution Jews were making to British society. But the Jewish People’s Council against Fascism and Anti-Semitism was also formed at this time. The Jewish People’s Council took action on the streets and engaged in anti-defamation work that exposed the political motives of the fascists. It worked closely with the National Council for Civil Liberties, organising joint conferences and having their speakers on the same platform at meetings. Other defence organisations were formed at around the same time, including a Jewish ex-servicemen’s organisation that soon had more than a thousand members.

Numbers of local residents resisted the BUF, and sometimes ended up in court. The Times of 25th June, 1937 reports that a fitter’s mate and St. Pancras resident, William Joseph Fairman, had been fined 40 shillings (£2) for “using insulting words and behaviour” by shouting “Smash Fascism! Down with the Fascists!” at a group of BUF marchers from Shoreditch and Stepney who were marching through St. Pancras opposed by “about 1,000 St. Pancras residents”. Fairman had been found with “Communist literature and application forms”. He must have been among many Communists who opposed the BUF locally. Anti-Fascist protest continued unabated until the outbreak of war and the banning of the BUF, along with the internment of its key figures including Mosley.

But after the War in the late 1940s there were attempts by Mosley and others to revive the British Fascist movement. Markets including Soho’s Berwick Street market were targeted for distribution of Fascist literature, although Hackney was the area of London most affected by the Mosleyites. Several other Fascist groups were operating at that time, many based in West London – perhaps as many as fourteen groups in London.

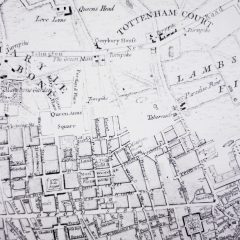

This drive was vigorously countered by various groups who by 1950 had aided in ending the ‘Union Movement’, as Mosley’s new group was called. The 43 Group consisted of Jewish men and women many of whom had served in the War and weren’t prepared to see Fascism take root again in British soil. Their story is compellingly told by one of the 43 Group’s key members, Morris Beckman, in his book, The 43 Group (1992). The 43 Group frequently met at an old and popular rendezvous for Jewish people: Lyons’ Corner House in Tottenham Court Road. Its office was in Panton Street, Soho.

A local lad, Sidney Spellman, was one of the 43 Group’s members. Brought up in Hanson Street, near Cleveland Street, he was an apprentice compositor in the print trade at the time of his involvement. Sidney writes in a letter quoted in The 43 Group:

My first involvement was attending fascist meetings Saturday afternoons at Notting Hill Gate. Victor Burgess [a well-known Fascist and anti-Semite who belonged to the pro-Mosley British Union of Freemen before joining the UM] spoke. … The platform was often knocked over … One meeting was the first night of the Succoth festival [a Jewish festival commemorating the Exodus from Egypt and taking place between late September and late October]. The fascists were about 2000 strong. They were protected by mounted and foot police who kept us apart. Next morning the Daily Graphic had a large front page picture showing me in the front row. I needed this to show my father why I had not been at synagogue the previous evening. (Morris Beckman. The 43 Group. 2nd ed. London: Centerprise Publications, 1993, p.200)

The 43 Group’s response to the Fascists was, “we were born here! We fought for this country and were trained to kill the same type of bastard coming back out of the woodwork. They, too, must be attacked and destroyed. If you can’t do it, we will!” (Beckman p.16) The Group helped to beat the Mosleyites by continual pressure on the Fascists often leading to violent confrontations at Fascist meetings; by working to gain support from people living in the most affected localities; and by obtaining advance information on the movements and intentions of the UM by successfully using infiltrators.

By 1950 Oswald Mosley had conceded that efforts to keep the UM going had failed, moving to Ireland in 1951. So, by 1950, those like Sidney Spellman who had fought to defeat post-war Fascism could feel that their job was completed.

Sidney Spellman and the 43 Group