The old Scala Theatre was brushed by cinema magic. As the journalist Lesley Blanch said in 1945:

it has always been associated with the cinema … One director told me how he came out from seeing one of the first great Griffith pictures, and reeled down Charlotte Street, punch-drunk by its impact. The Leader for 17th November, 1945

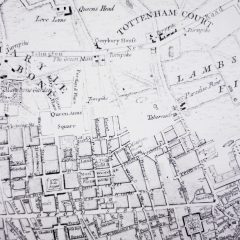

The site’s chequered history as an entertainment venue began way back in 1772, when The New Rooms was built for musical concerts on the corner of Tottenham Street and Charlotte Street. For years the building retained its musical nature under different names, but in 1802, as The Cognoscenti Theatre, it was used by an exclusive theatre club, The Pic-Nics, whose membership included the Prince of Wales.1 But this fashionable set quickly moved on, leaving it to be used as a circus! By the time Marie Wilton took over in 1865 it was known as the Queen’s Theatre but was nicknamed “The Dusthole”: the sort of place where the more uncouth patrons ate oranges in the gallery and squirted the juice over the posher customers in the circle.2

Under Wilton’s management the theatre flourished, hosting celebrated actors such as Ellen Terry. But by the 1880s the building badly needed renovating. It was left empty, then used by the Salvation Army. In 1903 it was bought by Distin Maddick, who extended the site and built what became the Scala, designed on a grand scale by Frank T. Verity. Architect’s plans included a large high-ceilinged restaurant occupying several levels of the theatre.3 The theatre’s name, Scala, was derived from the grand stairways leading from the dress circle to the stalls. Its first play was The Conquerer in September 1905 – but the venue was not a success and after the first few years only staged plays sporadically.

But in 1910 the Scala branched out into film, installing a cinematograph box. Charles Urban, a cinema pioneer, premiered his experimental Kinemacolor productions there from 1911. By hiring the Scala, Urban avoided risking money on a new-build cinema in what was then an unproven medium and gained a characterful building well-suited to his large-scale displays. Urban put on spectacular shows there such as the 1912 film of the Delhi Durbar welcoming King George V as the Emperor of India :

The Scala stage was turned into a mock-up of the Taj Mahal, with special lighting effects … a chorus of twenty-four, a twenty-piece fife and drum corps, and three bagpipes. 4

Urban’s films were hugely popular. The mix of cinematic and theatrical showbusiness sparkle must have been heady.

Theodore Brown, the inventor, also used the theatre in 1913 to show his Kinoplastikon films, an experimental form of screenless cinema originating in Germany where lifelike images appeared via reflected mirror projection. Luke McKernan says, “Kinoplastikon films were produced in a studio lined with black velvet (the actors had to be dressed entirely in white) on the roof of the Scala theatre.” 5 The Bioscope of 8th May 1913 comments:

The appearance of these amazing spirit creatures is curious. They resemble the figures of an ordinary cinematograph film, cut away from their original background with a pair of scissors, and set to caper and gesticulate …

In the 1930’s the Scala was home to live productions like Ralph Reader’s Gang Show, and staged recurrent seasons of Peter Pan from 1945. But that same year it also gained a new lease of movie life when The New London Film Society celebrated “Fifty Years of Cinema 1895-1945” with a Sunday programme of international classics. The opening film was Griffiths’ Birth of a Nation followed by greats such as Robert Weine’s The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, Eisenstein’s Potemkin and The Passion of Joan of Arc by Karl Dreyer. Lesley Blanch revealed that screenings included full orchestral accompaniment with a half-time break for the players. She reminisces about the times when live orchestras regularly played during feature films:

‘End of Part I!’ Up went the lights, the orchestra stumped out for half a pint of bitter … and audiences scrambled madly across each others’ knees to get seated again for Part II. The Leader 17th November, 1945, 19

Ten years later the Scala made more cinema history: it was the stage for the first-ever UK festival of Indian film organised by the Asian Film Society in 1955. Its opener was Sohrab Modi’s Queen of Jhansi, a take on the Indian Mutiny, attended by Peter Ustinov and Ingrid Bergman. Each show included a dance performance by Sitara, ‘The Kathak Queen’. Its most successful film, the first to obtain a British distribution deal, was Munna, mildly praised in the programme by Prime Minister Nehru, “I liked this film and consider it good from many points of view.” At a second festival in 1957 the Scala hosted Satyajit Ray’s masterpiece, Pather Panchali, drawing large audiences. A number of other film societies used the theatre at this time: in 1953 there had been a Festival of Soviet Films, arranged by the British-Soviet Friendship Society.

The success of the second Indian film festival prompted BBC television to make a half-hour documentary on Indian cinema, which, suggests Edward Hotspur Johnson in Sight and Sound Autumn 1988, was “possibly the first western television programme” on the Indian film industry. The theatre continued to show Indian films regularly: one Fitzrovia resident, Mohammed Moyen Uddin, has said he remembers going to Sunday afternoon screenings.

The Scala was finally demolished in 1969. It sounds like an eccentric place with something wonderful about it: it was even used by the Beatles in 1964 to film musical scenes for their film, A Hard Day’s Night. In live theatre it might not have made much of a mark, but instead it became a small but memorable part of the history of film in Britain.